The other day I commented on a piece that was run in the NYT on Wynne Godley and other Levy Institute scholars. Since then Paul Krugman has weighed in on the debate and Matias Vernengo has responded. Even though I’ve been known to be somewhat harsh on Krugman I think that the piece he wrote actually contains the seeds of a constructive conversation — unlike his typical approach to heterodox economists who are still alive, which is to dismiss them out of hand and ignore them. Krugman, it seems to me, is only comfortable debating the dead; not a particularly difficult task, mind you.

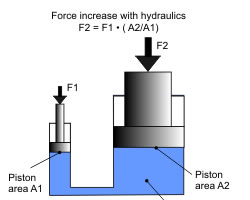

First of all, however, it should be noted that many of the errors that Vernengo points out Krugman as having made are indeed rather egregious. Krugman’s characterisation of what he refers to as “hydraulic Keynesians” as relying on a stable consumption function — that is, that consumption will rise and fall in line with income in a stable fashion — is entirely false. I have seen this mistake made many times before. In the General Theory Keynes lays out this argument, but it is clear from the context that it is a ceteris paribus condition that should be subject to empirical scrutiny (although Keynes mistakenly does say that this a priori condition can be relied on with “great confidence”). Here is the passage in the original:

Granted, then, that the propensity to consume is a fairly stable function so that, as a rule, the amount of aggregate consumption mainly depends on the amount of aggregate income (both measured in terms of wage-units), changes in the propensity itself being treated as a secondary influence, what is the normal shape of this function? (GT, Chapter 8, III)

As we can see, this really is just a ceteris paribus argument laid out to make a more general point. And as Vernengo correctly points out the Keynesian economist James Duesenberry updated this argument with his relative income hypothesis which is by far superior to Friedman’s permanent income hypothesis as championed by Krugman. (I should note in passing that I am currently waiting on data from the Post-Keynesian economist Steven Fazzari on consumption by income group that I have promised FT Alphaville I will write a post for them on. The data, from what I have seen, provides interesting insights into Duesenberry’s hypothesis. Watch this space).

Krugman’s other mistake is to discuss Godley’s work as if he adhered to the old Phillips Curve and was thus proved wrong by the inflation of the 1970s. As Vernengo points out Godley came from the Cambridge tradition which, in contrast to the neoclassical-Keynesians in the US, held inflation to be primarily wage-led. From this statement it is crystal clear that Krugman has not read any of Godley’s work (which leads one to wonder what gives him authority to pass comment on it). For example, in the book Monetary Economics, co-authored with Marc Lavoie, Godley devotes a whole chapter to inflation which they introduce as such:

Three propositions are central to the argument of this chapter. First, as we are now describing an industrial economy which produces goods as well as services, we must recognize that production takes time. As workers have to be paid as soon as production starts up, while firms cannot simultaneously recover their costs through sales, there arises a systemic need for finance from outside the production sector. Second, when banks make loans to pay for the inventories which must be built up before sales can take place, they must simultaneously be creating the credit money used to pay workers which they, and the firms from which they buy goods and services, find acceptable as a means of payment. Third, we are about to break decisively with the standard assumption that aggregate demand is always equal to aggregate supply. Aggregate demand will now be equal to aggregate supply plus or minus any change in inventories. (p284)

Inflation under these assumptions does not necessarily accelerate if employment stays in excess of its ‘full employment’ level. Everything depends on the parameters and whether they change. Inflation will accelerate if the value of [the reaction parameter related to real wage targeting] rises through time or if the interval between settlements shortens. If [the reaction parameter related to real wage targeting] turns out to be constant then a higher pressure of demand will raise the inflation rate without making it accelerate. An implication of the story proposed here is that there is no vertical long-run Phillips curve. There is no NAIRU. When employment is above its full-employment level, unless the [the reaction parameter related to real wage targeting] moves up there is no acceleration of inflation, only a higher rate of inflation. (p304)

So why did hydraulic macro get driven out? Partly because economists like to think of agents as maximizers — it’s at the core of what we’re supposed to know — so that other things equal, an analysis in terms of rational behavior always trumps rules of thumb.

May I ask you your opinion about SFC models? It is difficult to find a nuanced view on it.

Well, I think they’re good for didactic purposes but I’m highly skeptical of applying them directly to data. They were born out of Godely’s understanding of the dynamics of the national accounts and the flow of funds accounts and for that reason students can learn from them — provided it is made clear that they are highly stylised and not representative of reality.

I think you see this in Godley’s empirical work at the Levy Institute. When he did discuss his SFC models he always did so in a somewhat throwaway manner. The real thrust of his argument was intuitive and empirical.

Any empirical modelling has to be viewed with a certain amount of scepticism. But I don’t see why data driven SFC models should be any less representative of reality than any other type of empirical model. In fact, I think the particular attention paid to the long-run development of stock-flow relationships tells us important things about real economies that is often missed in other models.

You’re quite correct, Nick. They shouldn’t be any less representative of reality than any other type of model. The problem? That models aren’t built to represent reality. The same is true of the SFC models.

As Lance Taylor wrote in his essay on Godley:

http://cje.oxfordjournals.org/content/32/4/639.abstract

Indeed. It’s a terrible pity some of his “followers” don’t understand this.

I’m not sure what you have in mind when you talk about SFC models. Certainly, one could build SFC models that bear little resemblance to reality. But I wouldn’t say that is generally true. Ideally models should be constructed with an eye to how they relate to the data we observe and SFC models lend themselves quite well to this.

I’m pretty sure that this is how Wynne Godley saw things. He certainly treated the results of empirical models with caution, but I think there’s a difference between that and taking the view that they don’t have anything to say about reality.

Well, we could debate what Godley thought all day — I think he was of the same mind as me. I don’t think that models can be applied to reality at all. I follow Keynes on this. I’ve written a lot on this, but I guess this is one of the clearer pieces as it doesn’t get into the quagmire of probability and statistics.

” When he did discuss his SFC models he always did so in a somewhat throwaway manner.”

I think people in Levy did have a scratch SFC model unlike models in the book with Marc Lavoie which are big and have a lot of parameters but nonetheless they were using some SFC models.

Ramanan, yes, I’m aware of the Levy models. Zezza builds them. They have one for Greece and one for the US. I am highly skeptical.

They may have been built by Zezza, but they are clearly based on Wynne Godley’s work (with no disrespect to Zezza). WG started constructing empirical stock-flow models of the UK economy in the 1980s, building on some of the ideas implicit in the old CEPG model. The simple theoretical models were developed pretty much in parallel with the empirical ones. From what I have seen of the Levy models, they are very similar in construction to those early models of the UK that WG was working on 30 years ago.

Two things.

(1) For the sake of argument. I do not see any evidence that Godley ever used his models to do serious empirical work. They seemed more so footnotes. Maybe at some time during the 80s he thought it possible, I don’t know.

(2) That’s really not the issue here anyhow. It really doesn’t matter if Godley “believed” in the empirical models or not. The question is: are they useful? I see absolutely no reason to think that they are and, frankly, I find it odd that an entire generation of Post-Keynesians are beginning to break with Keynes, Kaldor, Robinson and others and are starting using models for empirical work. I still suspect it has mainly to do with (a) neoclassical techniques being forced on students that they then integrate and (b) access to funding.

I agree the issue is how useful such models are. This (and some other discussions I’ve had recently) prompted me to set out my own views: http://monetaryreflections.blogspot.co.uk/2013/09/on-role-of-models.html

FYI …

Wynne Godley in “Money And Credit In A Keynesian Model Of Income Determination”:

“Writings on monetary theory commonly rely solely on a narrative method which puts a strain on the reader’s imagination and makes disagreements difficult to resolve. The narratives in this paper will all describe simulations which are grounded in a rigorous model which will make it possible to pin down exactly why the results come out as they do”.

“I think he is basically correct in calling the Godley approach “hydraulic Keynesianism”

Btw, Coddington used the phrase hydraulic Keynesianism to describe Samuelson and IS/LM people and this terminology is popular because of the attention to his paper.

So in a sense it is incorrect to call Godley’s approach hydraulic Keynesianism. No doubt Godley used the phrase hydraulic in some paras in 4-5 places (because some of his starting results rely on work of Carl Christ etc for example the expression G/θ in his work) but the hydraulic analogy fails when extrapolated. Morris Copeland who invented the flow of funds tried to explain a lot why the hydraulic analogy is mostly incorrect although it has some delta usefulness and instead used the phrase money circuit.

I think it should refer to models that rely on stock-flow equilibrium rather than market equilibrium. That’s how Krugman is using it and, given that there is no very specific meaning given to the term, I’m on board with that.

“I do not see any evidence that Godley ever used his models to do serious empirical work.”

No!. In fact others have written texts on Wynne Godley’s models of the 70s and 80s for the UK economy. I have at least 3 books on this.

Plus check Arestis and Sawyer’s article on the book on Godley’s conference where they say something about the Levy model. The various projections in Godley’s papers are made out of models. Behind each future scenarios, there is also a growth number attached which is outputted from a model.

“The question is: are they useful? I see absolutely no reason to think that they are and, frankly, I find it odd that an entire generation of Post-Keynesians are beginning to break with Keynes, Kaldor, Robinson and others and are starting using models for empirical work.”

Kaldor himself attempted to write formal models on growth and what Godley and Lavoie try to do is go in the direction where Kaldor could not go far.

“I still suspect it has mainly to do with (a) neoclassical techniques being forced on students that they then integrate and (b) access to funding.”

Well that is a strange claim. Models have been useful in so many sciences and there is nothing neoclassical about using a model.Neoclassical economics rather fails because their relationships, lack of rigour etc. There is nothing neoclassical about a model. In fact it is laughable they call it a “model”.

In fact I have this to say. There is reality and all our attempts to understand them is some sort of mental model. It’s just that a formal mathematical model is one way to look at the world in addition to a method of narrative. A model also guides the narrative. In fact it has been a great experience for me to actually run some simulations in G&L’s models because one can see how a configuration changes in time. Also, since _any_ idea of what reality is different from what reality is, any such idea is actually a model – mathematical or non-mathematical.

(1) Yes, as I keep saying: Godley’s papers have a model crunch out a few numbers, but I think that these are not the main focus of the papers and are pretty throwaway.

(2) I have never seen an attempt by Kaldor to apply empirically a formal model of growth. Source?

(3) Have you read Tony Lawson’s recent excavation of the term “neoclassical”? https://fixingtheeconomists.wordpress.com/2013/08/27/what-is-neoclassical-economics-and-are-many-heterodox-economists-actually-neoclassical/

(4) Regarding the fact that models are used in other sciences: yes, one’s that deal with largely ergodic processes.

(5) I disagree that “all thinking is done in models”. That is an extremely dubious claim, philosophically. Although I hear it all the time from economists. I will do a post on this soon.

““all thinking is done in models”.

Extremizing to all thinking done in models to prove whatever you want to. It is not that all thinking is done in models but models do help.

“That is an extremely dubious claim, philosophically. Although I hear it all the time from economists. I will do a post on this soon.”

Sure! But do not use some silly Krugman model for illustration because they are not models at all.

“(2) I have never seen an attempt by Kaldor to apply empirically a formal model of growth. Source?”

Collected Essays, Vol 5:

Capital Accumulation And Economic Growth.

A New Model Of Economic Growth

Marginal Productivity And The Macroeconomic Theories Of Distribution

Vol 3

The Quantitative Aspects Of The Full Employment Problem In Britain

Vol 2:

Alternative Theories Of Distribution

These are not empirical models as in plug in some inputs and get outputs but are models, nonetheless.

Look again. You cannot say you are model-free or whatever. Your proposal of the Euro Area problems such with the one with Mosler implicitly assumes a model of the world (even though not in mathematical form) of what your future scenarios are and so do your posts on Latin America. For example, in your solution, there is no reason why Greece’s interest payments to foreigners won’t explode out of control to what is receiving from the ECB. Plus who decides how much the ECB will distribute to the countries in 5 years’ time?

Your ignorance of scenarios is a proof of why you are wrong. I like David Gross (a physicist)’s point made in a lecture that the greatest product of knowledge is ignorance. The good point of models is that although you cannot specify all future possible scenarios of the world, you have more control in discussing this. I am not sure of your hatred toward models.

For example you say:

“When considering economists and their models I have learned an important rule of thumb: an economist’s competence is inversely proportional to their need for a model. In addition to this, we can also add that as an economist’s need for a model increases we will often find that the model they rely upon becomes substantially more restrictive, lacking in nuance and stupid”.

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2013/03/philip-pilkington-hyperinflation-the-libertarian-fantasy-that-never-occurs.html#SD1OcJ2tC3K1MHD4.99

“Regarding the fact that models are used in other sciences: yes, one’s that deal with largely ergodic processes.”

Strange claim. In fact if you read G&L closely you will find how they think their models are evolving non-ergodically in time.

Again any view is a model of the world.

By “model” I mean a formal, deterministic view of the world that implies closure. All the rest follows from there. E.g. Kaldor examples are not “models” as I understand them etc.

G&L models, IF APPLIED, would require ergodicity. That was what my debate with Grasselli about whether Bayesian statistics required the ergodic assumption was all about.