A couple of days ago I wrote a quick post comparing Spain and the US after their recessions in 2007/2008 and the government responses. The post was based on the premise that the US government had engaged in active stimulus while the Spanish government had not. As Mark Sadowski pointed out in the comments section this was not correct; in fact, the Spanish government did engage in fiscal stimulus beginning in 2008.

So, what accounts for this discrepancy? Are we to assume that the US succeeded where Spain failed because of the QE program that the Fed undertook? I don’t think so. I think the explanation is far simpler and can be uncovered by looking in detail at the national accounts.

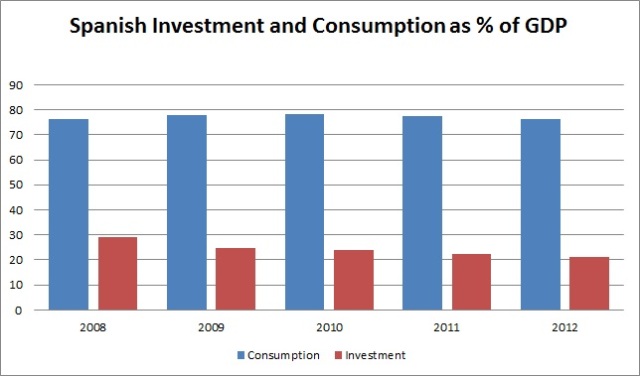

The first thing that we need to understand is the different structural make-up of each economy. We can do this by comparing how GDP is formed. The following graphs show to what extent GDP was weighted toward Final Consumption Expenditure and Gross Capital Formation — that is, toward consumption and investment. (All data is from the OECD and is expressed in constant prices).

The difference, as we can see, is rather striking. Throughout the period 2007-2008 the Spanish economy was far more reliant on investment than the US economy, which was substantially more consumption driven. Just prior to the recession in Spain consumption accounted for 76% of GDP while investment accounted for 29%. Meanwhile in the US just prior to the recession consumption accounted for 82% of GDP while investment accounted for 22%.

When we dig deeper into the data we find that key to this difference was the fact that housing construction (Dwellings) in Spain was a far more important component of GDP than was the case in the US. I have mapped their relative importance in the chart below. (Note that Spanish GDP peaked in 2008 while US GDP peaked in 2007 so I have taken each country at the pre-recession peak).

Again, the differences are striking. Just prior to the recession in Spain housing construction accounted for nearly 10.8% of GDP while in the US it only accounted for nearly 4.7%.

Now that we understand the relative structures of each economy it should be clear what happened during 2007-2008. As we can see from the chart below, housing construction fell from it’s pre-recession peak in both countries at fairly similar rate.

But as we have already shown the Spanish economy was far more reliant on this housing construction in the US. This, I think, is why the stimulus worked in the US while it did not work in Spain; simply put, the demand gap opened up by the bursting of the housing bubbles was far larger in Spain than in the US. Thus even if the Spanish government put a larger stimulus package in place it is not surprising that it failed where the US package succeeded.

1) “All data is from the OECD and is expressed in constant prices.”

Just a minor nitpick, but when calculating proportions it’s methodically more correct to do it in current prices, otherwise the proportions may not add up correctly and you can generate results that are obviously incorrect (e.g. net exports contributing to growth when trade is actually balanced). However, in this particular instance I don’t think it affects your main point one bit (so I’m just being anal).

2) It’s conventional wisdom that investment is more volatile than consumption and that residential investment is more volatile than overall investment.

But how does this affect macroeconomic performance? That all depends on how well policymakers manage aggregate demand. All other things being equal we might expect a high investment economy to be more volatile than a low investment economy, and a high investment economy to perform worse than a low investment economy in a recession. But if policymakers to a better job of managing aggregate demand in the high investment economy than in the low investment economy we might not find any difference.

3) Spain, Ireland and Greece had unusually high levels of residential investment prior to the recession and the decline in residential investment in those countries explains a great deal of the decline in GDP in those countries.

Residential investment peaked at 12.5%, 14.1% and 12.5% of GDP in Spain, Ireland and Greece in 2006, 2006 and 2007 respectively. This compares to 6.5% and 6.8% in the US and the Euro Area in 2005 and 2006/2007 respectively. Between 2008 and 2012 the proportion of GDP that was attributable to residential investment declined by 5.6%, 6.6% and 4.9% respectively. This compares to 2.3% and 1.1% inn the US and the Euro Area between 2007 and 2011 and 2008 and 2012 respectively.

Given Spain, Ireland and Greece are all members of the Euro Area and thus are subject to the same monetary policy we might very well expect them to perform worse than the Euro Area average once one accounts for differences in fiscal policy.

Before moving on it might be worth mentioning that both Spain and Greece have always had a large proportion of GDP devoted to residential investment. It averaged 7.3% in Spain from 1970 through 1999 and 15.3% of GDP in Greece from 1960 through 2001 according to AMECO. In contrast it averaged only 5.2% of GDP in Ireland from 1975 to 1997 and 6.3% in the EA12 from 1991 through 2002 according to AMECO. It averaged 4.7% of GDP in the US from 1955 through 1991 according to FRED. In fact prior to the recession residential investment had never been below 6.0% of GDP in Spain, and had never been below 9.0% of GDP in Greece. (Note also that the US set neither its highest (6.9% of GDP in 1950) nor its lowest (0.7% of GDP in 1944) rate of residential investment during the housing bubble.)

It also might be worth mentioning before moving on that the high levels of overall investment attained in Spain, Ireland and Greece attained before the recession (31.0%, 28.2% and 26.7% of GDP respectively) was exceeded by all of the BELLs (Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) as well as Slovenia although none of these countries had a peak rate of residential investment higher than the peak Euro Area average. Thus these countries, which are all either in the Euro Area, or are pegged to the euro, are subject to the same volatility problem as Spain, Ireland and Greece.

4) Fiscal policy explains the relative differences in nominal GDP (NGDP) performance of Spain, Ireland and Greece perfectly. (That is, within the confines of the ECB’s dreadful monetary policy, and given the fact these are all high investment economies, Spain’s fiscal stimulus *did* work.)

Consider the changes in Cyclically Adjusted Primary Balance (CAPB via IMF Fiscal Monitor) relative to 2008 (percent of potential GDP):

Year-EuroA.-Spain-Ireland-Greece

2009–(-1.8)–(-4.2)–2.6–(-4.9)

2010–(-2.0)–(-2.5)–5.3—-2.7

2011–(-0.5)–(-1.5)–6.8—-8.6

2012—-0.6—–1.5—8.1—11.9

And here is the nominal GDP of these entities indexed to 100 in 2008:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?graph_id=153157&category_id=0

Note that Spain had a more expansionary fiscal policy than the Euro Area average in calendar years 2009-11 relative to 2008 but it has underperformed the Euro Area in NGDP throughout. This can be explained by the fact that Spain is a high investment economy. Note also that Ireland had the most contractionary fiscal policy in 2009-11 relative to 2008 and performed the worst in terms of NGDP in 2009-2011. Greece went from having the most expansionary fiscal policy in 2009 to the least in 2012 relative to 2008 and its NGDP performance rank relative to the other two high investment economies matches its fiscal policy rank.

In short, subject to a persistent aggregate demand shortfall, high investment economies underperform relative to other economies, but fiscal policy can explain relative performance. Spain would very likely have performed worse relative to Ireland (throughout) and Greece (in 2010-12) if it had not been for its more expansionary fiscal stance.

5) Monetary policy can also explain relative performance among high investment economies.

All of the high investment economies I have mentioned so far are part of the Euro Area or are pegged to the euro. Thus they are all subject to the same monetary policy. The only advanced high investment economy not pegged to the euro that I could find is the small island economy of Iceland.

Investment as a percent of GDP peaked at 35.6% of GDP in 2006 in Iceland. Residential investment peaked at 6.9% of GDP in 2007, not at the same stratospheric levels as in Spain, Ireland and Greece but still higher than the Euro Area average. Investment declined from 24.6% of GDP in 2008 to 12.5% of GDP in 2010. Residential investment declined from 5.5% of GDP in 2008 to 2.3% of GDP in 2010.The decline in investment from peak was 23.1% of GDP in Iceland compared to 11.2% of GDP in Spain. Investment declined by 12.1% of GDP in Iceland and by 9.3% of GDP in Spain. The decline in residential investment during the recession was 3.3% of GDP in Iceland and 5.6% of GDP in Spain. So there was larger decline in overall investment in Iceland than in Spain although less of it was in the form of residential investment.

Here is NGDP in Iceland, Spain and the Euro Area indexed to 100 in 2008:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?graph_id=153176&category_id=0

As you can see, unlike in much of the advanced world, NGDP never fell in Iceland on an annual basis, and furthermore it rose by nearly 15% from 2008 to 2012 unlike in spain where it fell by over 5%. Iceland’s CAPB increased by about 10%, 14%, 17% and 19% of potential GDP relative to 2008 in 2009 through 2012 respectively. So Iceland’s fiscal policy has been very tight, tighter than either Ireland’s or Greece’s throughout.

Yes, real output and employment has yet to fully recover in Iceland, but the unemployment rate is currently only 4.8%, so given that and its relatively robust inflation rate, it’s impossible to argue that Iceland is suffering from an aggregate demand shortfall.

Substantive error:

“Investment declined by 12.1% of GDP in Iceland and by 9.3% of GDP in Spain.”

should read

“Investment declined by 12.1% of GDP in Iceland and by 9.3% of GDP in Spain during the recession.”

The inflation in Iceland was caused by a massive decline in the value of the currency.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Icelandic_kr%C3%B3na#Issues_affecting_the_currency

It’s a small open economy with a current account deficit of over 20% at the time of the crisis. When the currency fell import prices went through the roof. This is extremely common knowledge. It has nothing to do with monetary policy.

The Exchange Rate Channel is one of the most important channels of monetary policy. Changes in relative prices and wages are easily made via currency depreciation. Iceland experienced an enormous adjustment in prices and wages relative to the European core precisely through the fall in the krona.

Sweden and Poland underwent smaller depreciations in July 2008 through March 2009, with Sweden suffering a relatively mild recession and Poland avoiding one entirely. Spain probably needed a similar adjustment, but that adjustment will instead require years of grinding wage deflation in the face of high unemployment (unless there is a change in ECB policy).

You’re not serious, are you? Do you really think that the value of the Krona was more than cut in half because of the central bank’s monetary policy stance? Do you know anything about what happened to Iceland in 2008?

The Eurostat Price Level Index for Iceland rose from 18.7% above the EU-28 price level average in 2001 to 59.2% above the average in 2007, an increase of 34.1% in six years:

http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?query=BOOKMARK_DS-053404_QID_-24D77D4E_UID_-3F171EB0&layout=TIME,C,X,0;GEO,L,Y,0;INDIC_NA,L,Z,0;AGGREG95,L,Z,1;INDICATORS,C,Z,2;&zSelection=DS-053404INDICATORS,OBS_FLAG;DS-053404AGGREG95,00;DS-053404INDIC_NA,PLI_EU28;&rankName1=INDIC-NA_1_2_-1_2&rankName2=INDICATORS_1_2_-1_2&rankName3=AGGREG95_1_2_-1_2&rankName4=TIME_1_0_0_0&rankName5=GEO_1_2_0_1&sortC=ASC_-1_FIRST&rStp=&cStp=&rDCh=&cDCh=&rDM=true&cDM=true&footnes=false&empty=false&wai=false&time_mode=NONE&time_most_recent=false&lang=EN&cfo=%23%23%23%2C%23%23%23.%23%23%23

Thus the depreciation of the krona was widely viewed as desirable, if not inevitable. The following shows the krona-euro exchange rate corrected for HICP (the real exchange rate) set to 100 in June 2007:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?graph_id=153349&category_id=0

Even after the 36% decline in the real exchange rate between June 2007 and September 2008 the krona was probably still overvalued relative to the euro (and since 2010, the Price Level Index in Iceland has been consistently above the EU-28 average). Nevertheless, at that point the Central Bank of Iceland (CBI) decided that stabilizing the exchange rate was to be a key policy objective, otherwise it would become increasingly impossible to achieve the CBI’s inflation objective.

The attempt at pegging the krona to the euro in early October was initially botched due to the failure to impose capital controls (something which the Baltic States always effectively had during their pegs). It was this that precipitated the exchange rate crisis which was then brought under control by the imposition of capital controls, something the CBI should have done from the moment they decided to stabilize the exchange rate.

Thanks for the narrative Mark, I’m well aware of all the above. You may have also noted the extensive capital flight that actually caused the depreciation, assuming that we as economists are still actually interested in causality.

But let’s just be clear so that the key point doesn’t get lost here. You wrote:

And then went on to give the Iceland example. But of course monetary policy does not explain the high NGDP in Iceland. As you just now yourself admitted, the central bank in Iceland tightened monetary policy to try to stifle an inflation that was caused by a currency crisis that occurred around the beginning of 2008 after an extensive capital flight from the country.

In short: no, monetary policy cannot really explain anything, anywhere after the crisis. It was ineffective everywhere it was tried because, as I have been maintaining from the start, it is a very haphazard policy instrument. And the “market monetarist” faith in it is just that: faith, with no real empirical evidence beyond a few spurious relationships.

Yes, if I didn’t call you out on the currency crisis in Iceland you could easily have done regressions on NGDP and interest rates after 2009 and thus provided so-called “evidence” of market monetarist claptrap and I would imagine most people would have accepted it… This is in part because the market monetarist crowd have spread this ridiculous notion that NGDP is somehow a good measure of economic “progress” whereas in many countries such as Iceland the high inflation has been a huge problem for the country who at one time even considered trying to adopt the Canadian dollar to counteract the disastrous rise in import prices. If you’d used a standard measure for Iceland — i.e. real GDP — it would have been clear how bad the situation is there. And no, it is not one that can be solved with fiscal stimulus because the country has such bad balance of payments difficulties.

Market monetarism is truly the new monetarism in that it relies on dubious measures of economic progress and spurious relationships (both of these are tied up with one another). When you dig down into the market monetarist arguments they are almost wholly wrong and the results can be explained by a standard Keynesian framework — usually by looking at the external balance, the currency, the government fiscal balance and the extent to which investment fell prior to the recession.

It’s an important point to note that when the real terms of trade worsen substantially – particularly for an exporter – the state may have to step in and control what is imported. Clearly the price mechanism doesn’t ensure that what is needed is supplied.

Essentially you may need to implement rationing to ensure that your increasingly precious real exports are swapped for the right sort of real imports.

Another example of where price doesn’t eliminate excess demand in a manner useful to the society.

“You may have also noted the extensive capital flight that actually caused the depreciation, assuming that we as economists are still actually interested in causality.”

True, there was extensive capital flight between the time that the CBI attempted to peg the krona to the euro in early October 2008, and the imposition of capital controls in late November. But capital flight cannot explain the depreciation that the krona experienced prior to that for the simple reason that there were large capital *inflows* all during that time.

Capital flows were positive every quarter from 2007Q2 through 2009Q2. In fact in 2008Q4, the quarter of the currency crisis, capital inflows reached 20.8% of GDP, a rate of inflow only exceeded by the 31.1% rate reached in 2008Q1. The reasons for the krona’s depreciation from June 2007 through September 2008 are complex, but they have little to due to capital flight.

“As you just now yourself admitted, the central bank in Iceland tightened monetary policy to try to stifle an inflation that was caused by a currency crisis that occurred around the beginning of 2008 after an extensive capital flight from the country.”

To be clear, the currency crisis erupted *after* the CBI fumbled in its attempt to peg the krona. At that point investors quite rightly feared that the CBI had lost control of the exchange rate. And the move to stabilize the exchange rate was viewed as appropriate given year on year inflation was double digit and had been so since April 2008.

“In short: no, monetary policy cannot really explain anything, anywhere after the crisis. It was ineffective everywhere it was tried because, as I have been maintaining from the start, it is a very haphazard policy instrument.”

Then it seems exceedingly odd that everywhere that it has been tried, namely the US, the UK, Sweden, Poland and Iceland, NGDP growth has been far more robust than where it has not been tried, namely the Euro Area.

“This is in part because the market monetarist crowd have spread this ridiculous notion that NGDP is somehow a good measure of economic “progress” whereas in many countries such as Iceland the high inflation has been a huge problem for the country who at one time even considered trying to adopt the Canadian dollar to counteract the disastrous rise in import prices. If you’d used a standard measure for Iceland — i.e. real GDP — it would have been clear how bad the situation is there.”

To be precise, aggregate demand (AD) is nominal GDP (NGDP) when inventory levels are static (i.e. nominal Final Sales of Domestic Product). Thus for all intents and purposes AD is in fact virtually identical to NGDP. The whole reason for looking at NGDP is that it is the appropriate metric for measuring the effects of those policies intended to regulate AD, namely monetary and fiscal policy.

Real GDP (RGDP) can change due to shifts in short run aggregate supply (SRAS). Just as by itself inflation can tell us nothing about AD, by itself RGDP growth can tell us nothing about AD. And since the AD-AS Model was introduced by Keynes in Chapter 3 of the General Theory, I have no doubt that he would agree with this were he alive today.

Still citing Iceland in there… hmmm…

Maybe you should consider that the Euro Area has a single currency and thus is imposing austerity while countries with their own currencies — i.e. the ones that control monetary policy — have no such pressure. You know… maybe you’re engaging in “spurious correlation” here. Econometrics 101.

Or just keep running blind regressions on large swathes of data without engaging in any interpretation. I guess that’s what most economists do these days.

Anyway, this debate has descended into the pit. Good talking to you though. Keep the NGDP flag flying.

“Maybe you should consider that the Euro Area has a single currency and thus is imposing austerity while countries with their own currencies — i.e. the ones that control monetary policy — have no such pressure. You know… maybe you’re engaging in “spurious correlation” here. Econometrics 101.”

That might be true in the case of Sweden, which has not engaged in much if any fiscal consolidation. But according to the October 2013 IMF Fiscal Monitor, between 2009 and 2013 the cyclically adjusted primary balance (CAPB) of the US, the UK, Poland and Iceland has increased by 4.3%, 6.2%, 3.8% and 9.0% of potential GDP, whereas in the Euro Area it has only increased by 3.4% of potential GDP.

So, according to your CAPB measures the austerity has been worse in Europe? Yeah, thanks. We all know that. I’m from Ireland, you know, and I live in the UK.

So, austerity is worse in Europe. Maybe that’s the cause you’re looking for. Not eased monetary policy. Jeez, how many times do I have to say it: austerity is the cause of low growth in Europe relative to the US and the UK!!!

**Not that I think the CAPB is an acceptable measure, but however…

“So, according to your CAPB measures the austerity has been worse in Europe?”

An *increase* in a fiscal balance means fiscal consolidation is taking place. Thus when the CAPB increases more in one currency area than another that means more fiscal consolidation is taking place within that currency area.

Thus since 4.3%, 6.2%, 3.8% and 9.0% are all larger in magnitude than 3.4%, that means that austerity has been *worse* in the US, the UK, Poland and Iceland than in the Euro Area between 2009 and 2013.

More austerity in the US and UK than in Ireland then? And you wonder why I say don’t trust the CAPB?

It’s a garbage measure, as I’ve said from the beginning. Austerity has been fierce in Ireland. I had to emigrate. You’d be laughed out of the halls of Irish government making that case… and rightly so.

Anyway, I’ve had enough now. If you want to believe that austerity is easier in Ireland than in the US you can believe that if you want.

Also, if you’re going to use garbage measures like the CAPB you could at least disaggregate them and not talk about the Euro Area as a whole. The fiscal issues in Germany are very different from the fiscal issues in Greece.

“More austerity in the US and UK than in Ireland then?”

No. More fiscal austerity in the US, the UK, Poland and Iceland than in the Euro Area between 2009 and 2013.

Meaningless measure. Disaggregate.

“Also, if you’re going to use garbage measures like the CAPB you could at least disaggregate them and not talk about the Euro Area as a whole. The fiscal issues in Germany are very different from the fiscal issues in Greece.”

But we’re talking about monetary policy. Disaggregating currency areas would be illogical. It would make exactly as much sense as talking about the monetary policy of Arizona, Florida and Michigan.

You’re talking about monetary policy. I’m talking about fiscal policy. Anyway, I have better things to do. Think what you want. Bye.